By Michelle Cheng

~12 minutes

How Scientists are Using Worms to Learn About Humans

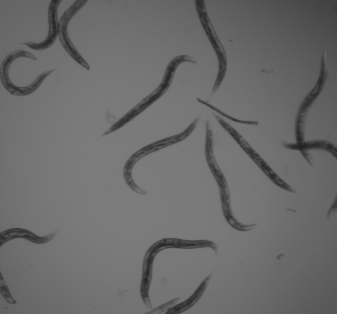

Worms and humans could not possibly be any more different. And yet, scientists have been studying C. elegans (caenorhabditis elegans) to learn more about the human body over 70 years. These unassuming worms have aided in groundbreaking findings in medicine for human diseases such as Alzheimer’s, AIDS, and stroke.

What makes C. elegans so valuable is not its complexity, but rather its simplicity. Because so many of its biological pathways are conserved in humans, this worm provides a uniquewindow into the fundamental processes of life, including cell division, gene regulation, neural signaling, and aging. With a transparent body, rapid life cycle, and a genetic makeup that mirrors much of our own, C. elegans has become an essential organism in modern biomedical research. Understanding how scientists use these worms can help us appreciate not just what we’ve already learned, but also the vast potential that still lies ahead.

What is C. elegans?

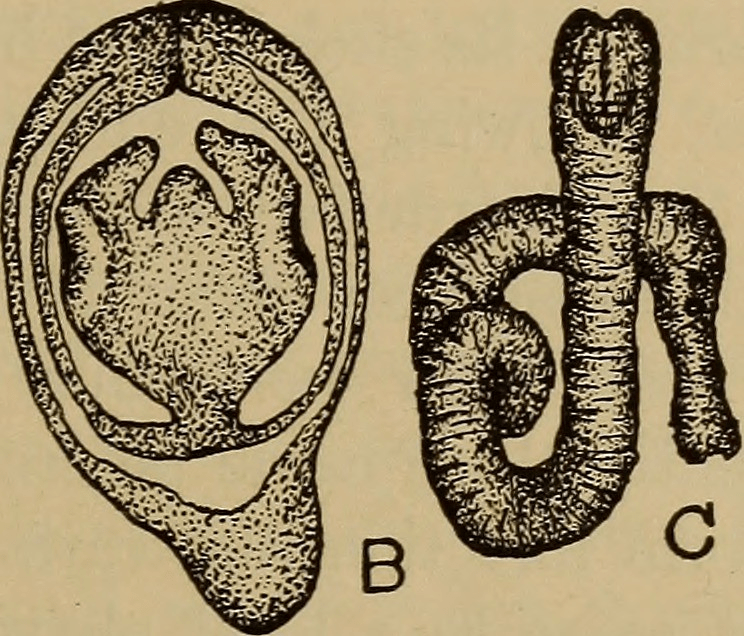

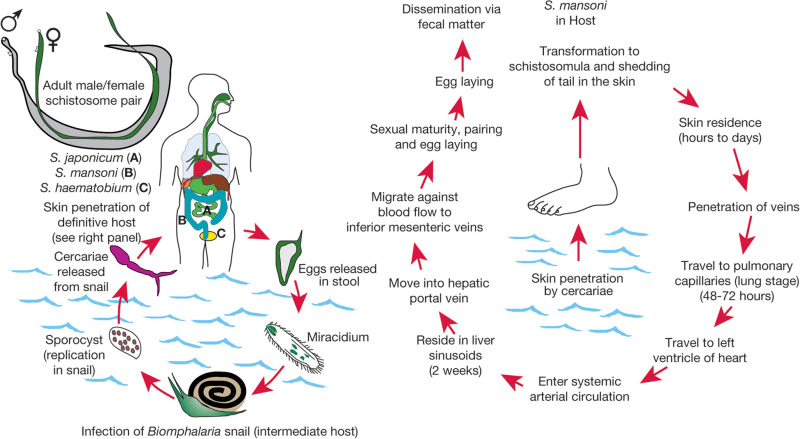

C. elegans is a free-living nematode that has become one of the most important model organisms in research. It measures approximately one millimeter in length and naturally lives in temperate soil environments, where it feeds on bacteria like e. coli. It is non-parasitic and exists in two sexes: hermaphrodites, which are capable of self-reproduction, and males, which occur at a less than 0.1% chance under normal conditions. The hermaphroditic reproductive mode allows for the maintenance of isogenic populations, which is advantageous for genetic studies.

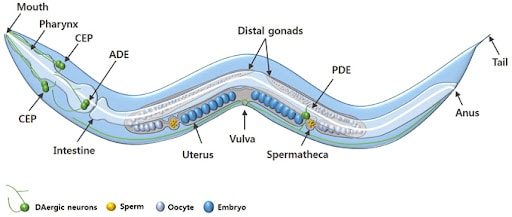

The adult C. elegans hermaphrodite has exactly 959 somatic cells while the adult male C. elegans has exactly 1,031 somatic cells. The worm’s relatively simple anatomy includes muscles, a nervous system, a digestive system, a reproductive system, and an excretory system. The organism develops through four larval stages before reaching adulthood, with a complete lifecycle taking just two to three weeks under laboratory conditions.

Genetically, C. elegans has a compact genome consisting of about 100 million base pairs across six chromosomes. It was the first multicellular organism to have its entire genome sequenced in 1998 in a project led by John Sulston and Bob Waterstons. Its genome is highly amenable to manipulation using a variety of modern techniques.

Why do scientists study C. elegans specifically?

First introduced into studies by Sydney Brenner in the 1960s to study neurological development and the nervous system, the nematode proved itself in the lab with its unique combination of genetic, anatomical, and practical features that make it exceptionally suitable for biomedical research.

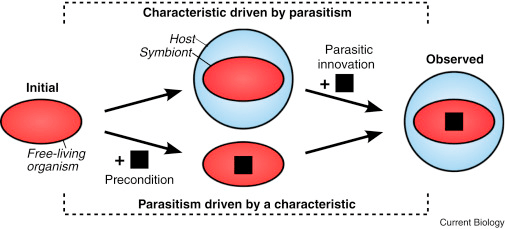

Remarkably, around 60-70% of human disease-associated genes have counterparts in the C. elegans genome, making it an incredibly valuable model for studying human biology. Many genes responsible for critical cellular functions are evolutionarily conserved between worms and humans. Therefore, scientists can manipulate the function of these genes in C. elegans to study their roles in disease without the complexity or ethical challenges of working with human subjects or higher animals like mice or primates.

Adult hermaphrodites’ cells, which remain the same in every single worm, each of which has been identified and mapped, allowing for detailed tracking of development, differentiation, and cellular processes. Its transparent body enables real-time visualization of internal structures, including neurons, muscles, reproductive organs, and digestive tissues. The worm, which has a simple nervous system of only 302 cells, is one of the only organisms where every neural connection is known. Additionally, C. elegans has a short life cycle of two to three weeks and is easy to culture in large numbers, making it especially convenient for developmental and aging studies.

How do scientists modify C. elegans in experiments?

Scientists modify and study C. elegans using four primary methods: RNA interference (RNAi), CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, transgenic techniques, and drug screening.

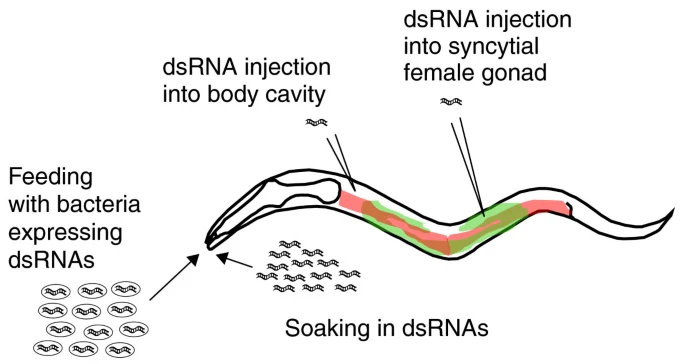

One of the most widely used techniques for modifying gene expression in C. elegans is RNA interference (RNAi). This method allows scientists to silence specific genes to observe the effects of their absence. In C. elegans RNAi can be easily administered by feeding worms with genetically engineered E. coli bacteria that produce double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) matching the gene of interest. Once ingested, the dsRNA activates the worm’s endogenous RNAi pathway, leading to the degradation of the corresponding messaging RNA and a reduction or elimination of the target protein. This method is highly efficient, non-invasive, and relatively easy to perform, making it ideal for large-scale genetic screens. Researchers can identify genes involved in key processes such as embryonic development, aging, metabolism, and neurodegeneration.

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized genetic research in C. elegans by enabling precise, targeted alterations to the genome. Scientists introduce a complex composed of the Cas9 enzyme and a guide RNA (gRNA) into the worm, which directs the Cas9 to a specific DNA sequence. Once there, Cas9 introduces a double-strand break in the DNA. The cell’s natural repair mechanisms then fix the break, and researchers can insert, delete, or replace specific DNA sequences. In C. elegans, CRISPR can create mutants mimicking human disease alleles or study regulatory elements of genes. This method provides a level of control that surpasses RNAi, as it allows for permanent and heritable genetic modifications. Scientists often inject the CRISPR-Cas9 components directly into the gonads of adult hermaphrodites, ensuring that the genetic changes are passed onto the offspring.

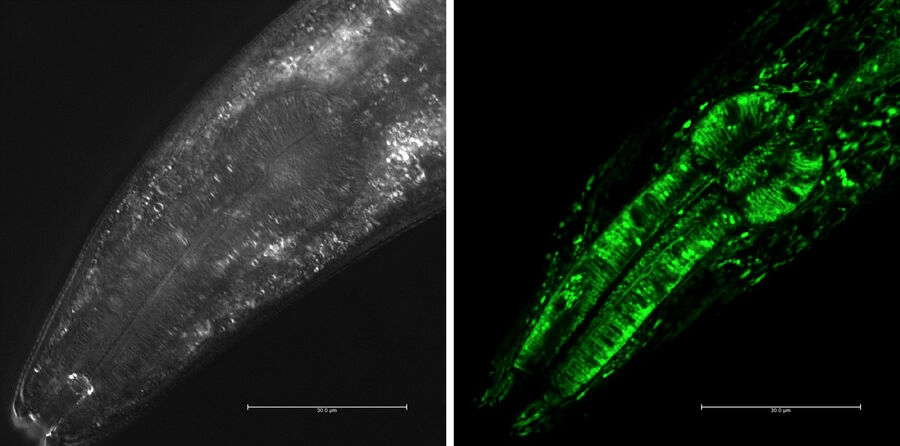

Transgenic techniques in C. elegans insert foreign DNA into the worm’s genome to monitor gene expression, trace cell lineages, or study protein localization. One common approach is to fuse a gene of interest to a reporter gene such as green fluorescent protein (GFP). When this gene is expressed, the fluorescent tag can be visualized in living worms using fluorescence microscopy. This allows researchers to observe where and when specific genes are active, how proteins move within the cells, and how cells interact during development or disease progression. Transgenes are typically introduced via microinjection into the syncytial gonads of adult worms, leading to the formation of extrachromosomal arrays inherited by the next generation. Stable lines can also be created through CRISPR or chemical integration methods. These visual tools are particularly powerful due to the worm’s transparent body, which makes it possible to track fluorescent signals in real time throughout the entire organism.

C. elegans is an excellent system for drug screening and environmental toxicology due to its small size, short lifespan, and genetic tractability. Researchers can test the effects of thousands of compounds quickly and cost-effectively. In these experiments, worms are exposed to chemical agents in liquid or on agar plates, and their survival, movement, reproduction, or specific cellular markers are measured to assess the biological impact. Using genetically modified strains that mimic human disease pathways, scientists can screen for drugs that alleviate symptoms or restore normal function. These tests provide an efficient first step in drug development, singling out promising candidates before moving onto mammalian models.

One of the most groundbreaking discoveries made using C. elegans was the genetic basis of programmed cell death, or apoptosis, a critical process in both development and disease. The research was led by Dr. H. Robert Horvitz at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Horvitz and his colleagues began studying cell death in C. elegans in the 1980s by tracing the fate of every cell in the worm’s body during development. They discovered that exactly 131 cells always die in the developing hermaphrodite and that this process was genetically controlled. Through genetic screening, Horvitz identified three core genes that regulated apoptosis: ced-3, ced-4, and ced-9. By inducing mutations in these genes, the researchers could either prevent or accelerate cell death in the worm. This revealed that cell death is not a passive consequence of damage, but rather an active, genetically programmed event. The mammalian counterparts of these genes, like caspases and BCL-2, were later discovered to play central roles in cancer, autoimmune diseases, and neurodegeneration, making this research foundational to modern medicine. Horvitz was awarded the 2002 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work along with Sydney Brenner and John Sulston.

In addition, C. elegans has contributed to our understanding of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s. One major study was led by Dr. Christopher Link at the University of Colorado in the late 1990s. Link developed a transgenic C. elegans strain that expressed the human β-amyloid (Aβ) peptide in muscle cells. This is the same peptide that forms toxic plaques in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients. In the study, the researchers observed that worms expressing Aβ developed progressive paralysis as they aged, mimicking aspects of human Alzheimer’s pathology. They then used this model to screen for genetic mutations and chemical compounds that could suppress the toxic effects of Aβ. Their work identified several genes involved in protein folding and stress response that modified Aβ toxicity. This demonstrated that C. elegans could be used as a fast and cost-effective in vivo system for identifying genetic and pharmacological modifiers of Alzheimer’s disease. The worm model has since then been adapted by numerous labs worldwide to study tau protein aggregation and mitochondrial dysfunction, expanding our knowledge of neurodegenerative pathways.

Another major discovery made using C. elegans was the link between insulin signaling and lifespan regulation. Dr. Cynthia Kenyon at the University of California, San Francisco, led a series of experiments in the 1990s that transformed the field of aging research. Kenyon’s team discovered that a single mutation in the daf-2 gene, which encodes an insulin/IGF-1 receptor, could double the worm’s lifespan. They found that when daf-2 signaling was reduced, it activated another gene, daf-16, which promoted the expression of stress-resistance and longevity-related genes. To test this, Kenyon used genetic mutants and tracked their development and survival across generations. The C. elegans with the daf-2 mutation lived significantly longer than their wild-type counterparts and were more resistant to oxidative stress and heat. These findings provided the first clear evidence that aging could be actively regulated by specific genetic pathways rather than being a passive deterioration process. Later studies found that similar insulin/IGF-1 pathways exist in mammals, including humans, opening new therapeutic avenues for age-related diseases, diabetes, and metabolic disorders.

So what does the future hold?

The future of C. elegans in scientific research is remarkably promising, with its applications continually expanding as technology and genetic tools advance. With the rise of CRISPR-Cas9, optogenetics, and high-throughout screening techniques, researchers can now manipulate C. elegans with unprecedented precision to study complex biological processes such as epigenetics, gut-brain interactions, and real-time neuronal activity.

In the coming years, C. elegans is expected to play an even greater role in personalized medicine and systems biology. Its potential as a predictive model for human gene function could aid in understanding the consequences of mutations found in patient genomes, leading to more tailored treatments. The worm’s short life cycle, fully mapped genome, and conserved biological pathways make it an ideal model for rapidly identifying new therapeutic targets and testing drugs, especially for age-related and neurodegenerative diseases. Despite its simplicity, this tiny nematode continues to open doors to complex human biology, proving that even the smallest organisms can have the biggest impact on science and medicine.