By Aravli Paliwal

~6 minutes

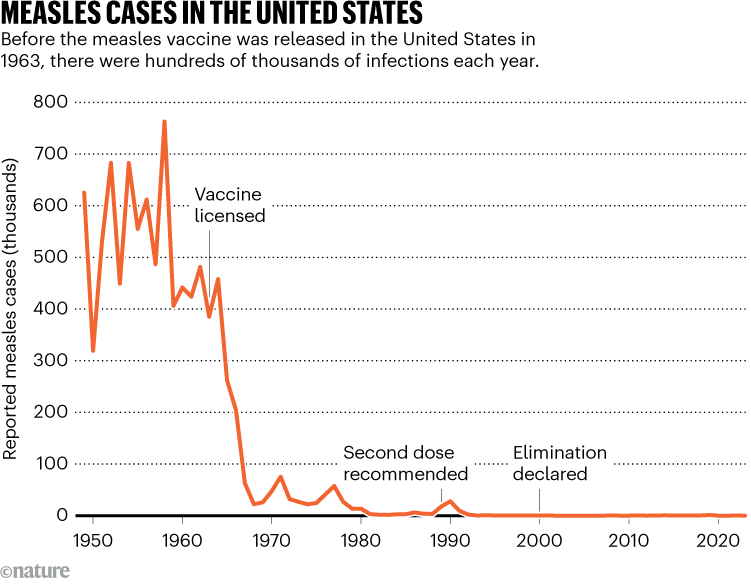

The United States is currently facing its greatest measles surge in almost thirty years, with 1200+ Americans testing positive for the disease so far this year. While some experts blame international travel, others believe vaccine hesitancy is the primary reason for this surge. However, to stay protected and stop the spread, we must first understand the science behind measles and what it takes to stay protected.

What is measles?

First documented in the early 12th century, measles ran rampant for centuries with hundreds of millions infected every year. An endemic disease, measles perpetually circulated and would flare up into cyclical outbreaks every 2-3 years. According to the National Library of Medicine,

“Measles […] caused more than 6 million deaths globally each year.”

To put this tremendous number into perspective, 6 million annual deaths is comparable to the population of the entire Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex getting wiped out every single year. Children under 15 were most vulnerable, and it was almost expectation that kids would experience the routine fever, cough, and blotchy rash before reaching adulthood.

How the Virus Spreads

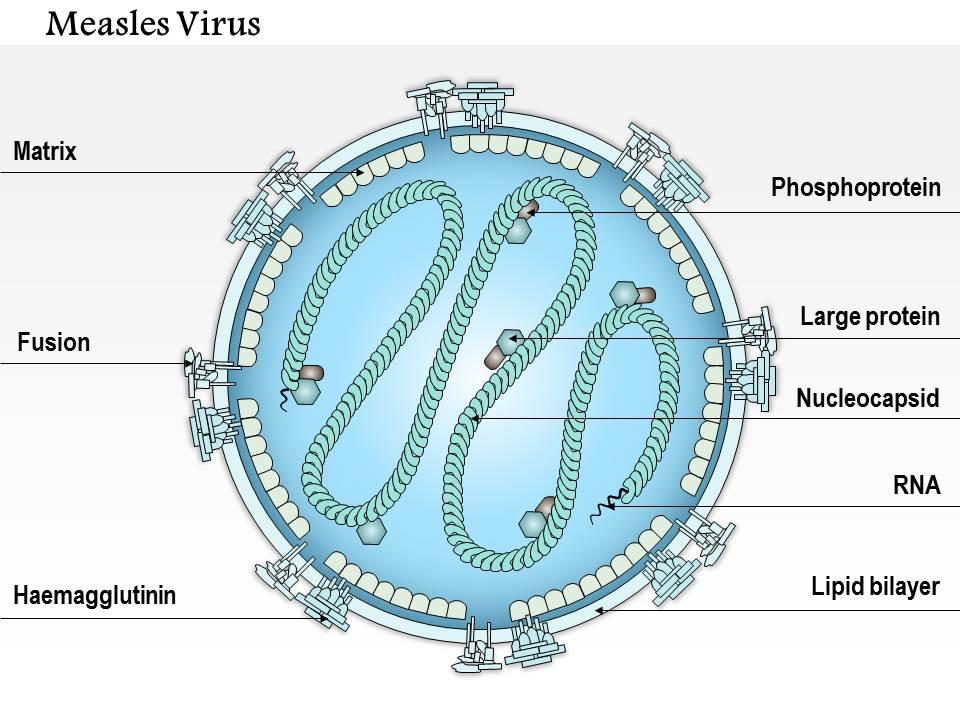

Often confused with smallpox and chickenpox, measles is an airborne pathogen that attacks cells in your respiratory tract as you breathe in the disease. The virus itself is composed of a single negative-sense RNA strand that is unreadable to human cells. However, measles carries a special enzyme that converts the previously unreadable virus into a positive-sense RNA, allowing proteins in our body to replicate and spread the disease.

The speed at which measles hijacks cells prevents the immune system from responding immediately, and groups measles together with other fast, aggressive negative-sense RNA viruses including influenza, rabies, and ebola.

Furthermore, measles is categorized as an enveloped virus. This means a lipid membrane envelops each cell and allows for easier access to infect healthy host cells. However, the measles virus exhibits one key vulnerability: soap and detergent can easily break down the fatty envelope, destroying its ability to infect.

Washing your hands and clothes significantly reduces the risk of virus from ever reaching your system, but remember, because measles is primarily airborne, sanitation does not completely prevent transmission.

How does the vaccine counteract the virus?

Though measles took the world by storm for centuries, in 1963 Dr. John Enders and his team developed the first measles vaccine. Often coined ‘the father of modern vaccines,’ Enders formulated the Edmonston-B strain, a killed virus vaccine.

The vaccine took the live measles virus and deactivated the disease’s genetic RNA so it could not reproduce, while preserving the outer proteins of the cell so the immune system could produce antibodies to combat the virus.

Despite its revolutionary effects, the Edmonston-B vaccination also presented major drawbacks. Immunity wore off over time, and people even developed ‘atypical measles,’ a form of measles with heightened symptoms including higher fevers, pneumonitis, and pain not typical of regular measles.

Therefore, 5 years after the initial Edmonston-B strain was drafted, in 1968 microbiologist Dr. Maurice Hilleman developed the Edmonston-Enders strain. This vaccine used an attenuated form of the 1963 Edmonston-B strain, by allowing the virus to grow in chick embryos, first. As the measles virus mutated to survive in chick cells, it slowly lost the ability to cause full-blown disease in human cells.

The final product? A live virus that infected your cells enough to train your immune system, but not enough to cause the atypical disease and heightened side-effects of the 1963 Edmonston-B strain.

A few years later, the MMR vaccine was created, combining defense against measles, mumps, and rubella in one shot. Two doses produced a 97% chance of protection against the diseases. Today, it is still recommended that children take two doses of the MMR vaccine; one dose as an infant, and another between 4 and 6 years old.

So why is there suddenly a spike in US measles cases?

As I write this article, there have been 1227 confirmed measles cases so far this year, with the biggest outbreak taking place in West Texas. There, 97 people have contracted the disease with two unvaccinated children dying, the first measles-related deaths in the US since 2015.

Overall, this spike in cases is accredited to decreased vaccination rates since the COVID-19 pandemic. According to John Hopkins University,

“Out of 2,066 studied [U.S.] counties, [in] 1,614 counties, 78%, reported drops in vaccinations and the average county-level vaccination rate fell 93.92% pre-pandemic to 91.26% post-pandemic-an average decline of 2.67%, moving further away from the 95% herd immunity threshold to predict or limit the spread of measles.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, public health staff were pulled from routine duties like immunizations to focus on COVID testing, contact tracing, and hospital coordination. According to UNICEF USA,

“As access to health services and immunization outreach were curtailed [due to the pandemic], the number of children not receiving even their very first vaccinations increased in all regions. As compared with 2019, […] 3 million more children missed their first measles dose.”

Going forward, efforts to close the immunity gap will depend on identifying under-vaccinated populations and ensuring routine and follow-up vaccinations. As more people understand measles transmission and how the vaccine works, we will be better equipped to respond, and the risk of future outbreaks can be reduced significantly.