By Bela Koganti

~10 minutes

November is about the three S’s: scarfing down Thanksgiving dinner, seeing family, and splurging on Black Friday. But we’d like to add a fourth: STEM! This November, we’ve advanced in everything from the environment to Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin, so here’s what you need to know.

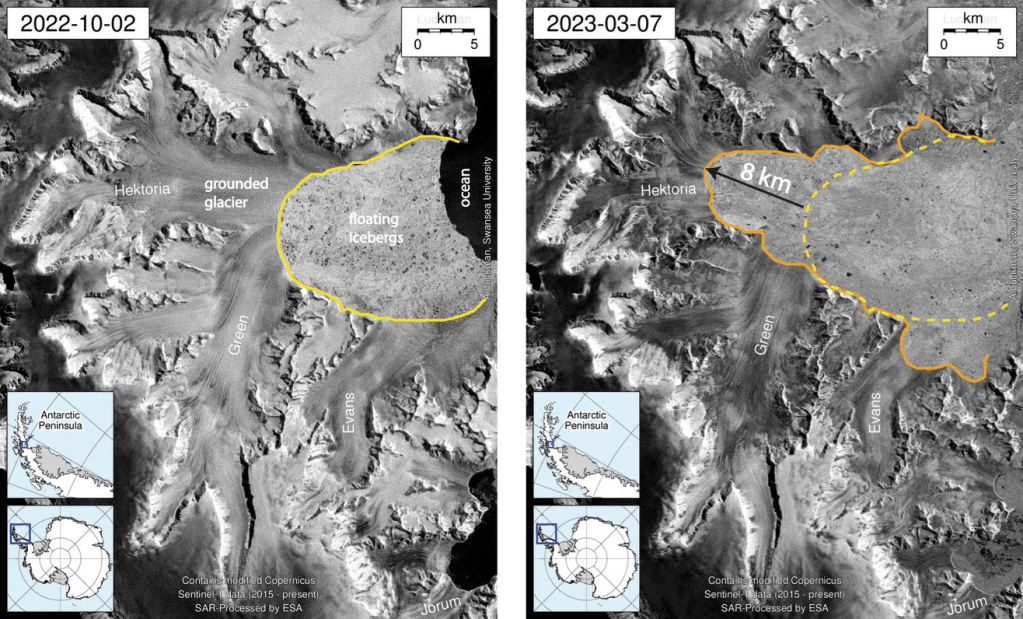

November 3: Gone Glacier

Antarctica’s Hektoria glacier recently became the quickest-retreating glacier in modern history, and a CU Boulder study published November 3 revealed how and why. From late 2022 to early 2023, over half of Hektoria disintegrated– that’s eight kilometers of ice, gone in just two months.

Essentially, the flat bedrock (or ice-plain) under Hektoria set it afloat as it thinned, causing the glacier to shed parts into the sea. Such a shedding process is generally called “calving”, and it’s pretty rare. Here’s why it happened in Hektoria’s case:

- In the past, glaciers resting on ice-plains dissolved hundreds of meters each day, so Hektoria probably experienced the same process.

- The ice-plain forced Hektoria to begin calving, and that exposure to the ocean created further cracks in the glacier. As the cracks met, they eventually calved the entire glacier.

- To confirm the process, scientists found a set of glacier-earthquakes that occurred in unison with the retreat.

With this new discovery of how and why Hektoria retreated, scientists can now predict and expect other glacier retreats. However, prediction does not equal prevention. These models show that continued warming, driven largely by human greenhouse gas emissions, will only accelerate this process. In order to help out, let’s follow this guide from the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research (UCAR) to minimize our CO2 emissions; I mean, we might just save a glacier.

November 8: Crispr for Cholesterol

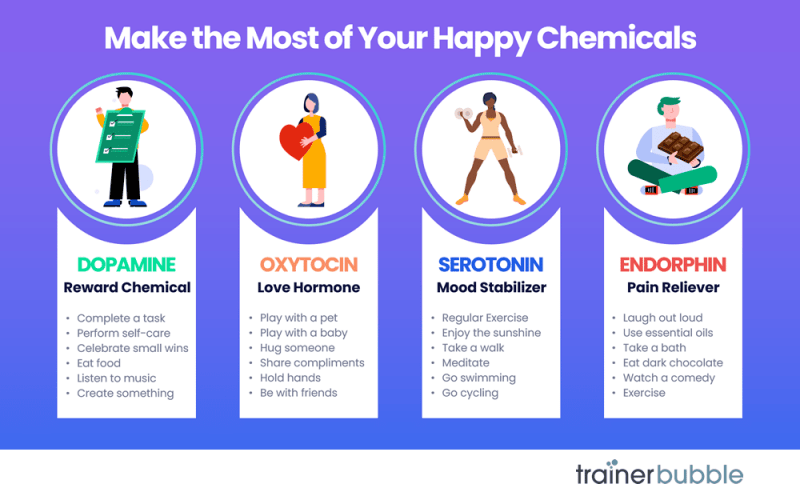

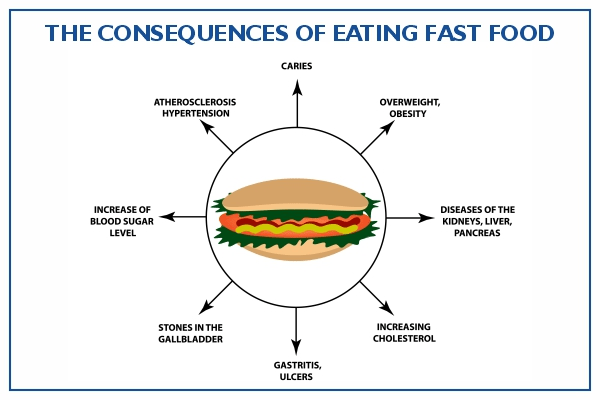

Cholesterol. We know it and sometimes fear it, but what is it? Cholesterol levels are determined by LDL cholesterol, a waxy compound that can clog arteries, and triglycerides, the most prominent type of fat in the body. Triglycerides can also harden arteries and artery walls. So, when we have high cholesterol, our arteries might be blocked and we have increased risk of heart attacks, heart diseases, and strokes.

Around 25% of adults in the United States have increased levels of LDL and triglycerides. Ouch. But never fear, Crispr is here! Crispr, a Swiss biotechnology company that deals with gene-editing, recently tested a new infusion and presented its results on November 8.

Their one-time infusion of CTX310, a therapy delivered by liquid nanoparticles, attempted to turn off ANGPTL3, a gene in the liver. Because some people are born with a mutated ANGPTL3 gene that safely protects them from heart disease, the Crispr scientists tried to replicate that. The highest dose given reduced triglyceride and harmful LDL by about 50% in two weeks, and the results lasted through the end of the trial.

With this initial success, Crispr plans to begin Phase II studies in 2026, and they hope to achieve an infusion that lasts a lifetime. Once safety of treatments is further explored and confirmed, CTX310 may even become a preventative measure. As senior author and chief academic officer of the Heart, Vascular, and Thoracic Institute at Cleveland Clinic Steven Nissen said,

“This is a revolution in progress.” -Steven Nissen

November 10: One of a Kind

The universe cannot be replicated. We follow no simulation, no set mathematics, and no algorithm. Who knew? Well, physicists, apparently. At the University of British Columbia in Okanagan, physicists proved that the universe cannot be simulated.

There’s a mathematical layer of quantum gravity dubbed the “Platonic realm” that creates even the concepts of space and time. However, these physicists proved that it cannot recreate reality purely with computation. Known as “Gödelian truths,” some things just cannot be understood with logic as they contradict themselves. Think about this for a minute: how would you prove the idea that “this true statement is not provable”? You can’t, and neither can a computer. Statements like this one exist all throughout our universe; when faced with them, computers’ logical algorithms fail.

Thus, computers cannot know and compute everything about our universe, so they cannot replicate it. We are one of a kind.

November 13: Bezos in Space

On November 13, Jeff Bezos launched Blue Origin’s New Glenn rocket out of Florida. New Glenn deployed two of NASA’s Escapade Satellites to measure Mars’ atmosphere and magnetic field, and, for the first time, its reusable booster successfully made it onto a landing pad in the Atlantic Ocean. Blue Origin is now the second company in the world to do so, with Elon Musk in first. Watch the landing here. Okay, check back in 22 months—hm, that’s September of 2027—when the satellites arrive at Mars!

November 14: Crispr for Cancer

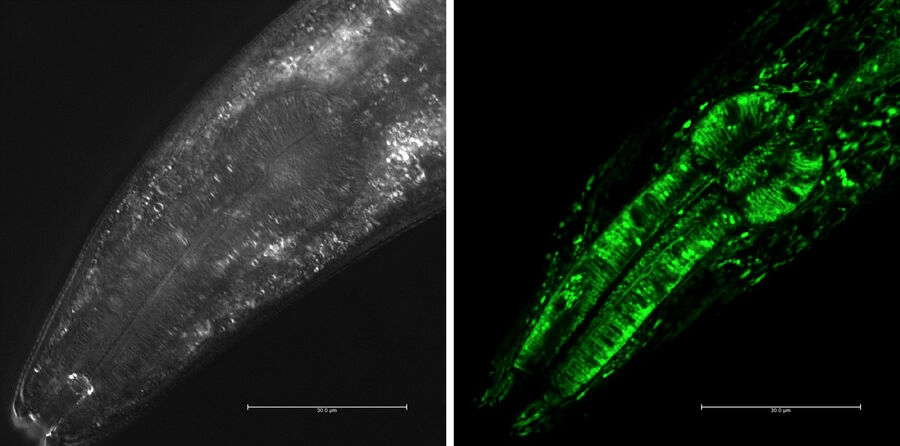

And for the second time in one article, Crispr’s here! This time, however, it tackles chemotherapy resistance in lung cancer. A gene called NRF2 can cause resistance to chemotherapy in some cases of cancer, so Crispr scientists looked at disabling it in lung squamous cell carcinoma, an aggressive type of lung cancer that makes up around a quarter of all lung cancer cases.

They infused R34G, a mutation in NRF2 that can regulate cellular stress reactions; when NRF2’s is overactive, it causes cancer cells to resist chemotherapy, so they used R34G to subdue NRF2’s behavior. Even when they only calmed NRF2 in less than half of tumor cells, it still reduced tumors and improved chemotherapy response.

“The power of this CRISPR therapy lies in its precision. It’s like an arrow that hits only the bullseye,” Kelly Banas, lead author of the study, said. As Crispr will continue to perform and study trials, R34G might just be the future of cancer treatment.

November 18: Gemini 3’s Release

We’ve all seen the AI overviews embedded into Google’s search results. You’re just wondering how long to bake your snickerdoodles for, but the AI’s answer ranges from 8 minutes to 25. What? Then, you look and see twelve recipes referenced. Huh? There’s no way it’s that difficult, you wonder. Yeah, we’ve all been there.

However, Google just launched Gemini 3, and they proclaim it their “most intelligent model” yet. Maybe we’ll get a more precise answer on those snickerdoodles now! More confident than ever in Gemini 3, Google embedded it into its search engine on the first day of its release, which they had never done before. Normally, they gradually implant new versions over weeks, or even months.

Gemini 3 also brings new features to the table. Or, well, to the phone. “Gemini Agent” can book travel plans, organize your overwhelmed email, and do other multi-step jobs. Additionally, they updated the Gemini app to respond to prompts with answers so thorough they look like websites.

Well, if you’re looking for a new AI model, Gemini 3 may very well be what you need. And if you’re looking for ridiculously incorrect and vague answers to make fun of, the jury’s still out on whether Gemini 3 is the platform for you or not.

November 18: A Milky Way Model

We already discussed computers’ inability to model our universe, but I never said anything about the Milky Way! Researchers from the RIKEN Center for Interdisciplinary Theoretical and Mathematical Sciences (iTHEMS) in Japan, The University of Tokyo, and the Universitat de Barcelona in Spain managed to accurately simulate 100 billion stars over the course of 10 thousand years.

These researchers trained an AI model using high-resolution simulations, and it eventually managed to predict resulting gas expansions. Thus, it created a simulation of the galaxy’s overall dynamics as well as its smaller phenomena. Previous models of the universe would struggle to predict on a small-scale, but this new one can do exactly that. Also, it did so quickly! In just under 3 hours, it created a simulation of the galaxy over 1 million years.

This new model could become popular for making other simulations that need small- and large-scale accuracy. Like lead researcher Keiya Hirashima said,

“This achievement also shows that AI-accelerated simulations can move beyond pattern recognition to become a genuine tool for scientific discovery—helping us trace how the elements that formed life itself emerged within our galaxy.” -Keiya Hirashima

November 18: Antimatter Aplenty

Have you noticed that this is the third event from November 18? Sounds like a hat trick to me! Anyways, CERN’s Antimatter factory recently undertook a new project called the ALPHA experiment, and they published their findings on November 18. Essentially, they managed to create over 15,000 antihydrogen atoms in under 7 hours.

Antihydrogen is the most basic form of atomic antimatter, and antimatter is a substance with the same mass and particles as another substance but opposite charges. For example, antihydrogen has the same mass and particles as hydrogen, but hydrogen’s protons have positive charges and its electrons have negative charges while antihydrogen’s protons have negative charges and its electrons have positive charges. When antimatter and matter meet, they destroy each other, creating an immense amount of energy. Antimatter is normally found in particle accelerators, cosmic rays, and medical imaging, but it’s fairly rare as creating it is a lengthy process.

However, with the ALPHA team’s new method, they’ve managed to make antimatter 8 times faster than normal. Normally, the process involves creating and trapping antiprotons and positrons separately before cooling and merging them together to form antihydrogen, but ALPHA’s unique success came from the way they create their positrons. The general problem with creating antimatter is that trapped positrons refuse to stay still once trapped, and they don’t cool down enough. So, the ALPHA team approached the antihydrogen by adding laser-cooled beryllium ions to the positron trap. The beryllium makes the positrons lose energy through sympathetic cooling, which cools the positrons to around -266 °C and makes them more likely to merge with the antiprotons and form antihydrogen, creating more antimatter.

Scientists thoroughly study any antimatter they can get, so, with this new abundance, they plan to study gravity’s effect on antimatter in the ALPHA-g experiment. Stay tuned because they may discover new properties and behavior of antimatter, which wouldn’t be possible without ALPHA’s new process.

Okay, that’s all I have for November. Consider this my holiday gift to you. Enjoy December, and come back for Stemline’s next recap!