By Katherine Johnson

~13 minutes

Have you ever had a parasite? Maybe you ate an unwashed fruit, had an open wound, or even stepped on something you shouldn’t have. Nevertheless, parasites are everywhere and more common than you may think. In this article, we’ll go over parasites as a whole; including a review on what they are, theories on evolution, and a deep dive into a specific parasite. Overall, parasitism is one of the most complicated relationships seen in nature, and whilst it’d take a mountain of explanation to understand it all, hopefully this article can deepen your current understanding and offer some insightful information.

What Are Parasites?

By definition, parasites are organisms that live off of another organism or “host”. There are many “species” or categories of parasites, ranging from utterly harmless to ultimately fatal. Some of the more common parasites you may have heard of include tapeworm, roundworm, pinworm, etc. While there are countless ways to get infected, tapeworm for example, only needs its eggs to be accidentally swallowed . Fortunately such cases are rare in developed countries like the U.S. Additionally, these parasites are objectively easy to get rid of. Albendazole is a very common medication used to treat parasitic worm infections, and taking a few doses should cure the disease. Oftentimes, albendazole is crucial in mass drug administration as an attempt to control and lessen cases of infection, especially within developing countries.

So what happens when you get a parasite? Well, it is impossible to give one direct answer. Say you are infected with a common intestinal worm, perhaps unknowingly you have ingested pinworm eggs. Some symptoms might include gastrointestinal issues, vomiting, abdominal pain, extreme itching, and even irritation, all common with other intestinal parasites. You go to the doctor, get some blood work, and thankfully they diagnose you, treat you with albendazole, and everything is back to normal. But what about when it’s not that simple?

Some parasites are much more dangerous, and at times, even incurable. Malaria, a very widely known global health concern, is a single-celled parasite spread by mosquitos. In some cases, such as that of Plasmodium falciparum (the most dangerous type of malaria) once infected, it can take only 24 hours to kill. While there are treatments and improvements in the medical world for malaria, developing countries are still struggling with the disease to this day. Another deadly parasite is brain-eating amoeba or Naegleria Fowleri. Found in infected waters such as lakes, this parasite enters the brain through the nose while you are swimming. While it is extremely rare, fatality rates are nearly 100 percent. Naegleria fowleri destroys the brain tissue causing swelling and oftentimes complete coma. Once the symptoms set in within a week of infection, it will take roughly five days until death. Unfortunately, there are countless more of these dangerous parasites including schistosomes, which we will cover later. However for now, let’s see how these parasites came to be.

The Evolution of Parasites

Though there are countless theories determining the exact evolutionary path or origin of parasites, there is no factually known truth. Overall, the study of evolution of organisms is an extremely difficult and unending task. To truly form a complete cycle of evolution you have to not only know the events that took place, but their total effect and order., Unfortunately we cannot go back into the past, but, there are some pretty strong theories regarding parasite evolution.

It is safe to presume that parasites arose millions of years ago from previously freeliving organisms. Many researchers believe that the majority of present-day parasitic life forms evolved after being ingested by their host. This theory, called ‘freeliving ancestors’, describes how freeliving organisms evolved to survive within their host by gaining their needed nutrients from within the host’s stomach. As mentioned earlier, some of the most common or well known parasites, such as the tapeworm, show stark similarities with this theory.

On the other hand, another well known potential theory is that the parasite-host relationship may have formed from a predator-prey relationship, where the parasite acts as the predator. Ancestors of such parasites have been found to have collected similar nutrients from their prey as parasites collect from their host. This theory is common in ectoparasitism, in which the parasite lives within, or on, the host’s skin.

Another theory to consider are facultative parasites. This represents the “hybrid” of parasitic characteristics and regular freeliving organisms. They provide the possible transitional state, or the “evolutionary stepping stones” within the transition to full blown parasitism. Facultative parasites can survive both on their own, and within, or on, a host. While dissecting facultative parasites as a whole calls for a separate discussion, it is important to understand a few things, for one: phenotypic plasticity. This refers to the flexibility of an organism’s phenotype, or observable characteristics. An organism with strong phenotypic plasticity has the ability to adapt more fluidly to its environment. For example, a facultative parasite may increase survival under specific conditions and overtime adapt on favorable heritable variations (in this case: parasites), also known as the Baldwin effect. Similar to the Baldwin effect, genetic assimilation, which represents phenotypic plasticity under specific conditions as well, is more set in place. This implies that eventually the organism’s plasticity will decrease, and the trait will no longer need the environmental trigger for it to show as it becomes fixed or stuck in place.

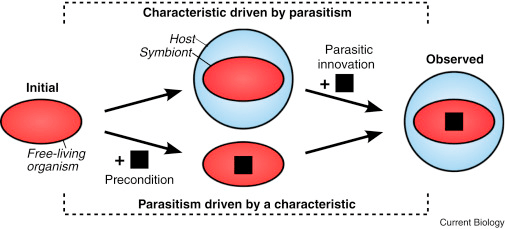

Once again, even with immense research and evidence, the exact path of evolution for parasites is difficult to place. Even with potentially knowing events that were detrimental to the evolutionary path, we still cannot specifically know which traits may have caused what. An interesting metaphor would be to think about how “noses might not have been selected to carry glasses.” While the characteristic of having a nose is useful for wearing glasses, it certainly didn’t evolve for that reason. Likewise, just because an organism has a quality that relates to parasitism, it may have nothing to do with it. For example, some traits we may have thought were specific to the evolution of parasites, have been found in completely different freeliving organisms with no real connection. Additionally, a parasitic trait can evolve in different ways as well. For example, the image below demonstrates the inverse relationship between various characteristics and parasitism.

Parasites: Today’s World

There are many misconceptions when it comes to parasites. Admittedly, parasites are utterly terrifying, so intense phobias and even psychosis aren’t farfetched. However, these false beliefs can lead to incorrect, useless, and even sometimes harmful homemade “treatments”. For example, have you ever heard of a parasite cleanse? A parasite cleanse is a form of detoxing the body through supplements, diets, or drinks. They frequently include different types of herbs, oils, and other supplements. These “treatments” are not medically necessary nor are they FDA approved. There is no evidence of these cleanses treating any parasites, and sometimes they can be harmful to your gut, causing other issues. If you believe you may be infected with a parasite, it is important to get proper medical help. That being said, let’s look into the current state of the medical world in relation to parasites.

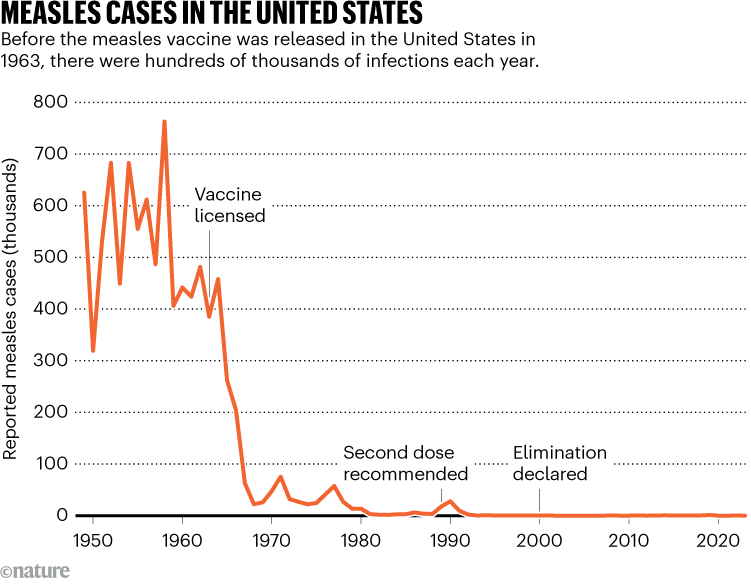

According to the World Health Organization, or WHO, approximately one quarter of the world’s population is infected with some type of intestinal worm, with even higher rates in developing countries. Although this statistic might seem concerning, there have been many improvements in the medical world, as well as constant research being done. For one, the mass drug administration system, as mentioned once earlier, is seeing vast improvements with providing ample medicine and treatments to those who need it. In particular, nanotechnology, the method of manipulating matter at the near-atomic scale, has helped tremendously in targeted drug delivery. Deeper research regarding genes and interactions of parasites with the host, is assisting in the making of treatments and vaccines. Whilst parasitic infections remain a problem today, there is much hope to help the issue decline within the future.

Schistosomes

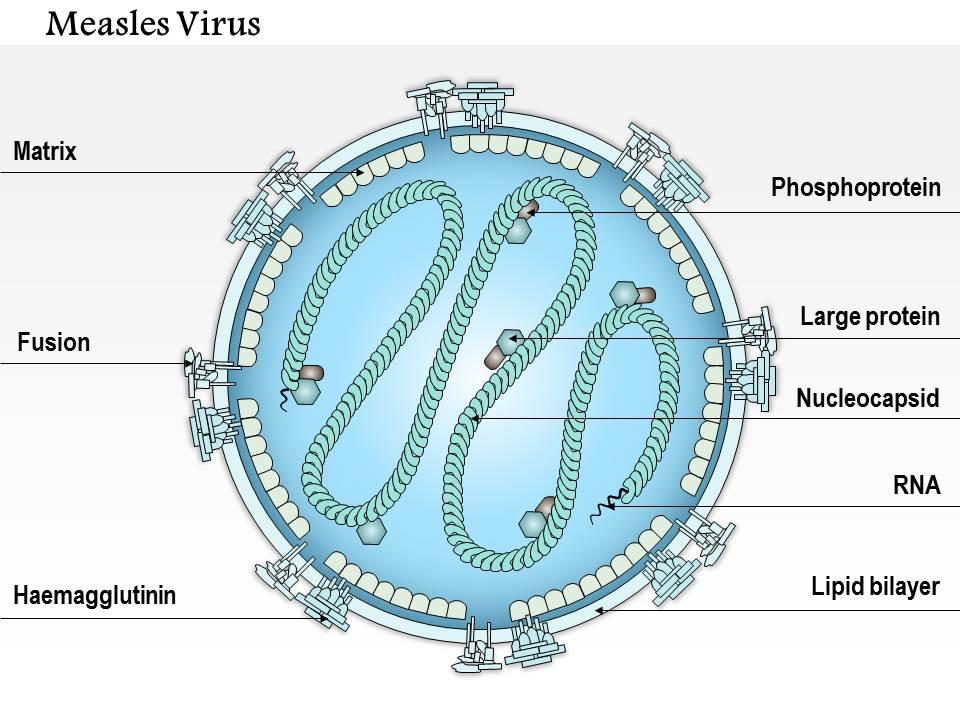

By now you have read through much information about parasites, specifically what they are, their evolution, and even some medical overviews. So now let’s take a deep dive about a specific parasite: Schistosomes. Schistosomes are a type of parasitic flatworm, distinctively known as blood flukes, and are the root of a terrible, oftentimes chronic disease called schistosomiasis. So what do you need to know?

Schistosoma are believed to have originated in the supercontinent of Gondwana around 120 million years ago, from their early parasitic ancestors, which primarily infected hippos. Interestingly, they began their life by primarily infecting a snail, parallel to their life cycle today, which you’ll read about later. From that point, through host migration, they traveled to Asia and Africa, where they are primarily found today. Eventually, the parasite evolved into other forms, more specifically schistosoma, predominantly infecting humans.

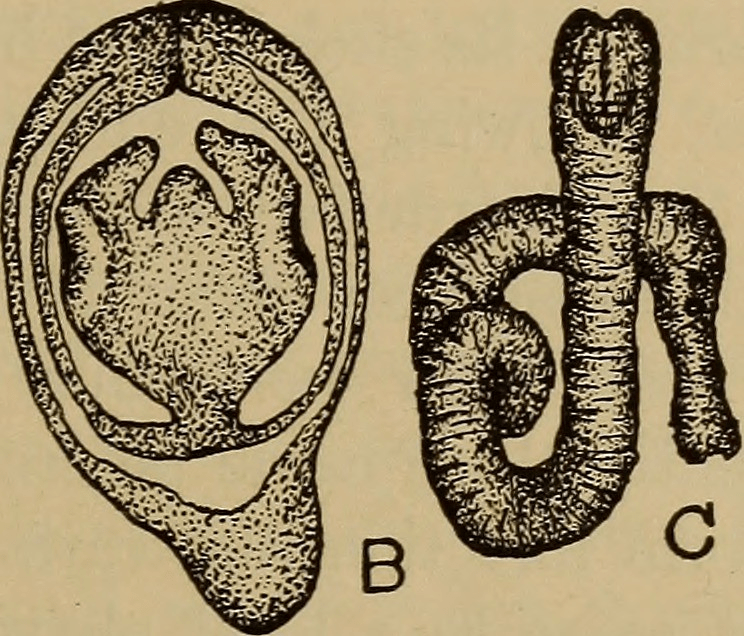

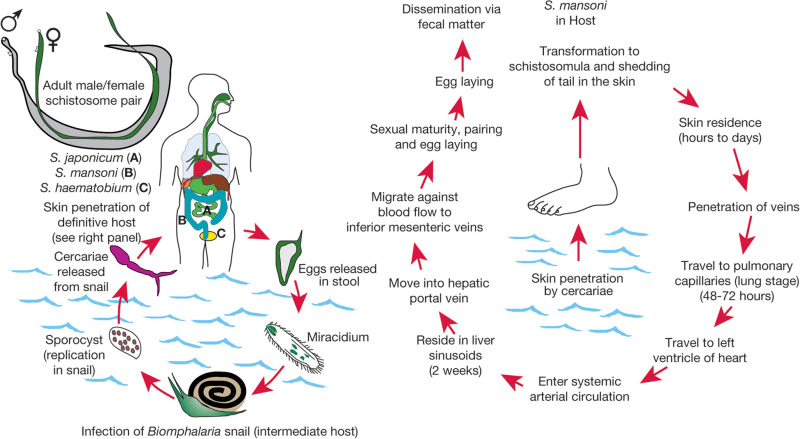

The life cycle of schistosoma has many stages, including two hosts. First, eggs are passed down from the previous host, through urine or stool, into water. These eggs, which then hatch into larvae, must now find their first host: a snail. Within these snails, the schistosoma continues to mature, releasing once again into water. As you are harmlessly swimming or bathing in seemingly clean waters, the schistosoma penetrates the skin, entering and infecting your body. From that point, they travel to your liver, where they fully mature into adult worms, and travel to the veins in the intestines or bladder to mate soon after. At this point you could have been infected for potentially months. Other than a slight skin irritation where they had entered your body previously, you don’t start showing symptoms until you get Katayama fever or the acute stage of schistosomiasis, lasting for a couple weeks.

Katayama fever is a hypersensitivity or immune complex reaction to the eggs being deposited in the body’s tissue. Symptoms of this stage are categorized by fever, abdominal pain, cough, muscle and joint pain, and so much more. At this point the disease is still possibly reversible. Treatments such as preziquantel are common for treating this disease and can help those infected formulate a full recovery. However, some people don’t necessarily show symptoms until it’s too late. For instance, in 2021 an estimated 176.1 million out of 251.4 million people were not treated on time.

The next stage is chronic Schistosomiasis. While technically the worms can be killed through specific treatment, they can cause irreversible organ damage with life long affects. Furthermore, the long lifespan of the adult worms can make it exceedingly difficult to treat. These worms can live in the body for over a decade, laying hundreds of eggs daily. While these eggs are produced in order to be released in the urine and stool, they frequently get trapped in the tissues of your organs. As they get trapped, the body’s immune response causes extreme inflammation in the organs, primarily the liver, bladder, and intestines. Alongside many other implications due to the lodging of the eggs, such as fibrosis (the formation of scar tissue), can lead to organ failure, increased risk of cancer, and ultimately death.

Schistosomiasis: Potential Future

Those with schistosomiasis often spend their lives in and out of hospitals. As time goes on, their bodies begin shutting down or falling victim to other illnesses. Schistosomiasis is an extremely hard disease to deal with, infecting more than 200 million people worldwide. Developing countries in Africa and Asia struggle tremendously, especially without access to clean water, or the inability to receive necessary treatment.

Though the probability of completely eradicating the disease within the near future is low, thankfully the number of infected is generally decreasing. As immense efforts are being made globally, better access to medication, as well as sanitary environments are readily being provided. Additionally, extensive amounts of research are helping find out more about schistosoma to better our treatments and potentially develop a vaccine.

Conclusions

Overall, while parasitic infections are fortunately majority of the time treatable, there is so much more to them than what one might think. In this article we were able to cover plentiful information about parasites, their evolutionary history, and the terrifying reality of Schistosomiasis, so with this knowledge, it is time to make a real impact. Below, there is a link to a GoFundMe page, where you can help Recy Abellanosa, a mother, wife, and teacher who is struggling with the effects of schistosomiasis. By donating, you will be able to take some of the financial burden off her family as she fights the disease. As a final remark, I highly encourage you to learn more about these organisms, as well as keep yourself and others around you educated in the current scientific and medical world.

Link to GoFundMe:

https://www.gofundme.com/f/support-recys-urgent-medical-needs