By Bela Koganti

~ 14 minutes

This October, STEM has reached new heights in astronomy, medicine, and awards. So, here’s an outline of what you need to know to stay informed.

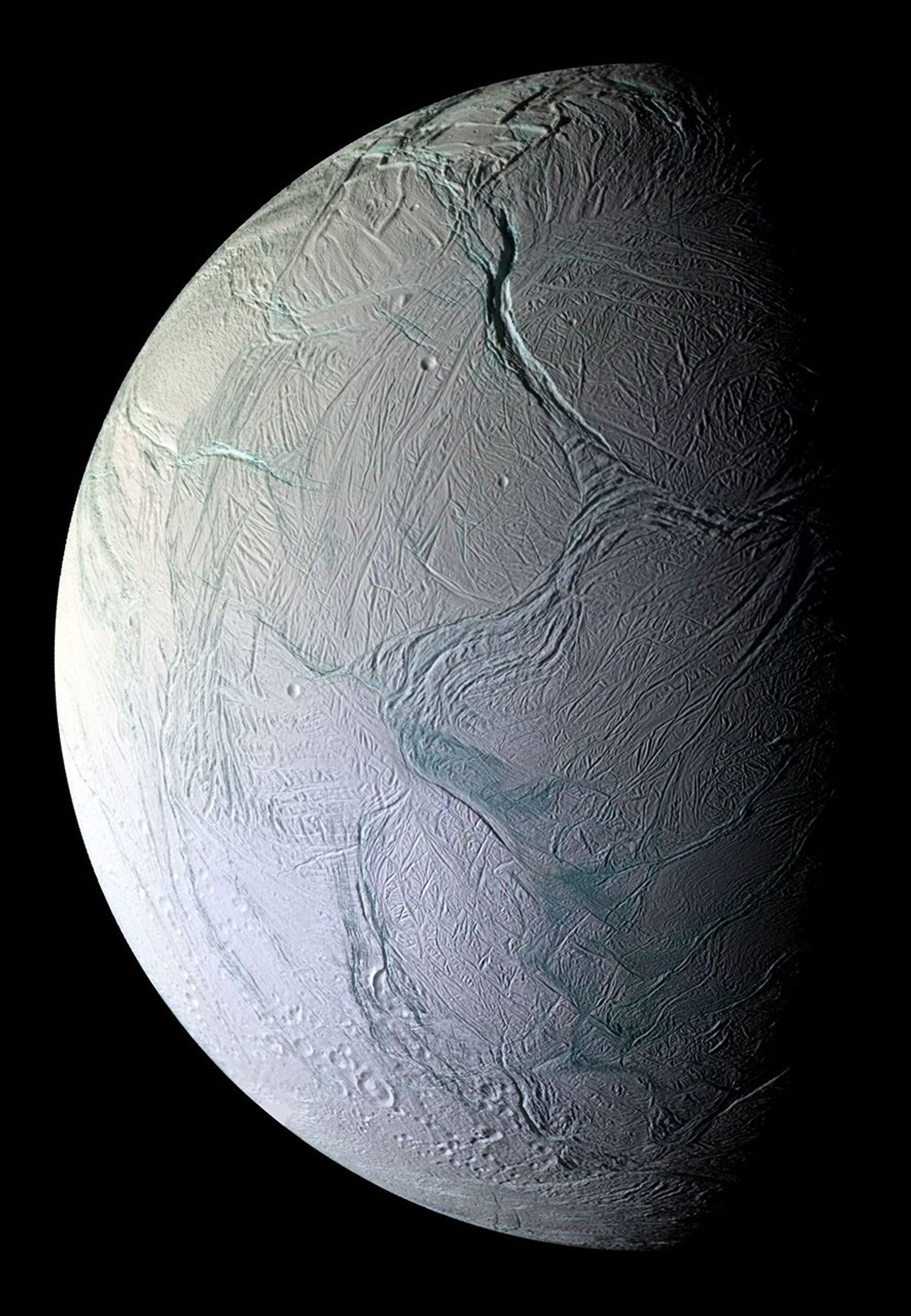

October 1: Enceladus

Saturn already has the highest number of known moons in our solar system, with 250, but it could also become the only planet with a habitable moon. Greedy, right? The 2005-2017 Cassini-Huygens mission to Saturn revealed clefts in the surface of Enceladus (one of Saturn’s moons) that shoot out water vapor ‘plumes’ into space as a ring (dubbed the E-ring) that circles Saturn. These clefts are believed to receive their water from an ocean below Enceladus’ surface. When the Cassini spacecraft flew through the plumes as they sprayed, it collected ice grains. Since the mission, scientists have been researching these grains, and they’ve found that Enceladus’ plumes hold carbon-containing molecules like aliphatic, heterocyclic esters, alkalines, ethers, ethyl, possibly nitrogenic, and possibly oxygenic compounds. They published their most up-to-date findings this October 1.

To break all this down, these carbon-containing molecules basically mean that the moon Enceladus might have the potential to house life. But don’t get too excited— it’s also possible that these molecules only become organic due to radiation, where ions in Saturn’s magnetosphere chemically react with the E-ring particles. To find out the truth, the European Space Agency might send an orbiter to Enceladus to sample fresh ice. Their orbiter wouldn’t arrive till 2054, so I suppose we’ll just cross our fingers till then.

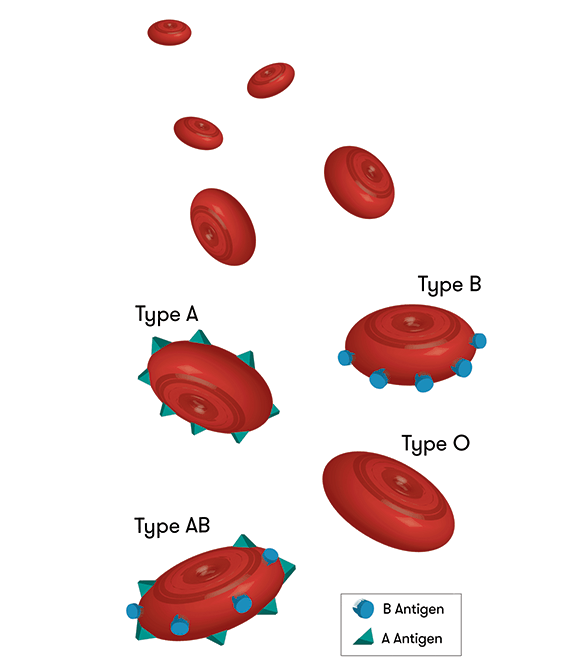

October 3: From Type A to Type O

We all know and love universal blood type O, but what about those who actually have it? For kidney transplants, type-A positive, -B positive, and -AB positive patients can receive their own respective type and type-O; however, type-O patients can only receive type-O kidneys. Thus, when these other patients receive type-O kidneys, people with type-O lack donors, end up waiting two to four years longer for their kidneys, and often die during the wait. Oh, and let’s not forget that type-O patients comprise over half of the kidney waiting lists!

Scientists from the University of British Columbia have been tirelessly studying this catastrophe for over a decade, and they published their first successful transplant this October 3. They managed to place two reactive enzymes in a type-A kidney so that the kidney changed to universal type-O. Sugars that coat organs’ blood vessels determine blood type, so they created an enzyme reaction to strip away the defining sugars. While past conversions have needed live donors and changed antibodies within patients, compromising their immune systems, this new method changes the kidney itself and uses deceased donors.

So, here’s what happened in their transplant test:

- Scientists converted a type-A kidney using the enzymes

- Placed the kidney in a deceased recipient (with the family’s permission)

- Days 1-2: the body showed no signs of rejecting the kidney

- Day 3: a few of the type-A attributes reappeared, which is a slight reaction, but nothing as severe as in previous conversions

- The body showed signs of tolerating the kidney anyway

- Success!

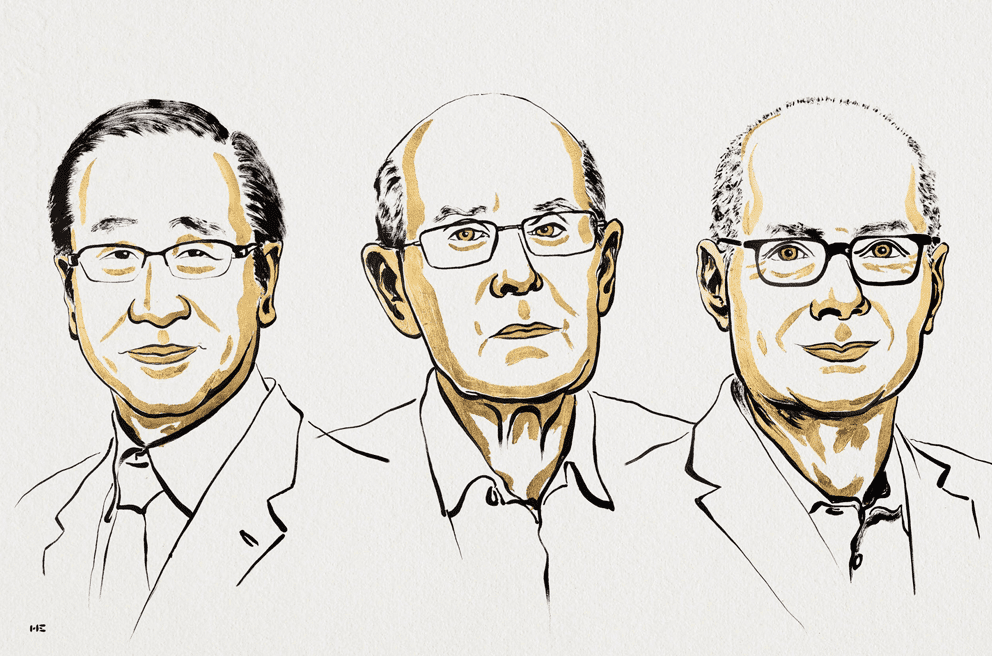

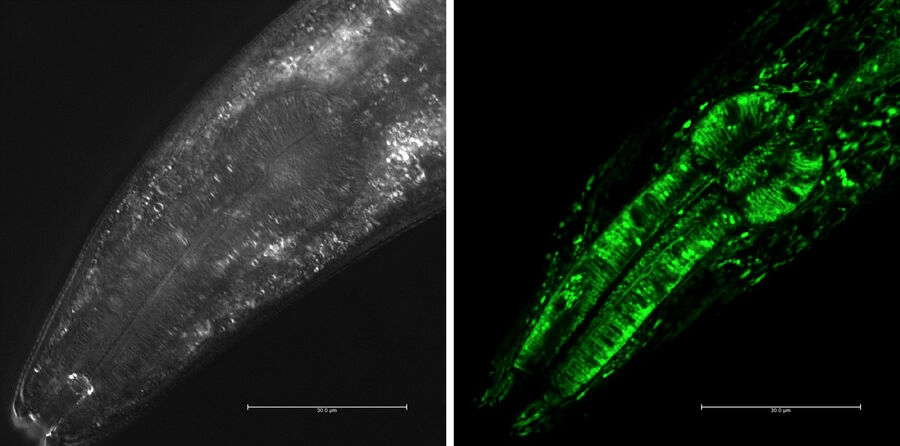

October 6: 2025 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

This year, the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine has been awarded to three people! Mary E. Brunkow, Fred Ramsdell, and Shimon Sakaguchi earned it for their advancements on ‘peripheral immune tolerance’, the mechanism that ensures the immune system doesn’t hurt the body. Essentially, peripheral immune tolerance prevents humans from having all kinds of autoimmune diseases. However, prior to these three, scientists had no real understanding of why or how this system worked. Brunkow, Ramsdell, and Sakaguchi built on each other’s findings to discover ‘regulatory T cells’, the agents behind peripheral immune tolerance.

Here’s how they did it:

- 1995: Sakaguchi debunked the popular theory of ‘central tolerance’ by discovering a new group of immune cells.

- 2001: Brunkow and Ramsdell explained why a certain type of mice was particularly defenseless against autoimmune diseases. They found that strain to have a mutation in what they dubbed their ‘Foxp3’ gene, and they showed that humans have a similar gene, which also causes an autoimmune disease when mutated.

- 2003: Sakaguchi showed that the Foxp3 gene dictates the growth of the cells he previously found. These cells became known as ‘regulatory T cells’, and they supervise cells in the immune system as well as the immune system’s tolerance of the human body.

All this is awesome, but let’s see how their discovery actually impacted modern medicine. Scientists have found that regulatory T cells can actually protect tumours from the immune system, so, in this case, they are looking for a way to dismantle the cells. However, to combat autoimmune diseases, scientists can implant more regulatory T cells into the body to help prevent the immune system from attacking the body. So, just as Ann Fernholm proclaimed, “they have thus conferred the greatest benefit to humankind.”

October 7: 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics

Get this: another trio received the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics! The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences bestowed the honor onto John Clarke, Michel H. Devoret, and John M. Martinis for their experiments demonstrating quantum physics within a larger system. Quantum physics, or quantum mechanics, allows tunneling, which is when particles pass through barriers. Normally, the effects of quantum mechanics become negligible once they start working with large particles, but Clarke, Devoret, and Martinis showed that tunneling can still happen in a larger system.

Just like with our last trio, here’s how they did it:

- 1984-1985: They experimented with passing a current of charged particles through a controlled circuit containing superconductors. They found that the multiple particles acted like one large particle when going through the superconductor. The quantum part of this was that the system used tunneling to go from zero-voltage to a voltage. So, they concluded that quantum mechanics can still cause tunneling in a macroscopic system.

And why do we care? Well, Olle Eriksson, the Chair of the Nobel Committee for Physics, said, “It is wonderful to be able to celebrate the way that century-old quantum mechanics continually offers new surprises. It is also enormously useful, as quantum mechanics is the foundation of all digital technology.” I don’t know about you, but I think I’ll take his word for it.

October 8: 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Our LAST Nobel Prize trio of October comes in Chemistry! Susumu Kitagawa, Richard Robson, and Omar M. Yaghi received the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for their ‘metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)’. These frameworks are from their new molecular construction, where carbon-based molecules link together metal ions so that the two form MOFs, which are essentially porous crystals. Scientists can then manipulate these MOFs to take in and guard particular substances. MOFs can also create chemical reactions and direct electricity. So, with these MOFs, scientists can design materials with particular functions of their choosing.

You know the drill– here’s how they did it:

- 1989: Robson began testing the properties of atoms by combining copper molecules with four-pronged molecules, and this created porous crystals similar to MOFs. However, these MOF impersonators were unstable and needed someone to fix them.

- 1992-2003: Enter- Kitagawa and Yaghi. From his experiments, Kitagawa concluded that MOFs could be changed and modified as gases could run through them. Then, Yaghi made a stable MOF and showed that they could be manipulated to have new properties.

Since their discoveries, scientists have made tons of their own unique MOFs, each equipped to solve a different problem. We can thank MOFs for giving us a safer Earth. I mean, any kind of chemical substance that can make clean water, grab carbon dioxide from the air, or produce water from desert air sounds like a good one to me.

October 11: The Surprising Link Between COVID-19 and Anxiety

Covid. The word that teleports Gen-Z right back to online school in pajamas, Roblox, and Charli D’Amelio. We all know and hate it, but did we realize that it might be affecting future generations who weren’t even alive in 2020?

A study published on October 11 revealed that male mice who contracted COVID-19 birthed children with more anxiety-like behaviors than those of uninfected mice’s children. Basically, COVID-19 changes RNA molecules in the male’s sperm, which then dictates his children’s brain development. In female offspring specifically, their brain’s hippocampus region, which deals with behaviors including anxiety and depression, was altered. The authors of the study believe that these changes may cause increased anxiety levels.

Okay, okay. Remember: this study was done on mice, not humans. More research is needed to see if humans will experience similar effects, but for now, we’re safe.

October 12: Light Years Away

“A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away…” Wait, what? A long time ago? Evidence suggesting that the closest alien civilization may be 33,000 light-years away did come out this October 12, but for the estimate to be feasible, the civilization would need to have already existed for at least 280,000 years. Yeah, that feels like a long time ago. And don’t worry about the far, far away part– I’d call 33,000 light-years pretty far.

At a recent meeting in Helsinki, research was shown indicating such a possibility. Here’s the criteria for a planet to have extraterrestrial life and actually sustain itself:

- Carbon dioxide in the atmosphere (so photosynthesis can work and support life)

- An atmosphere of at least 18% oxygen (complex animals need more oxygen, and there must be enough oxygen for fire because blacksmithing must happen to technologically advance)

- Average lifetime of about 10 million years (so they can exist at the same time as us)

- Already existed for at least 280,000 years (so civilization can develop and they can exist at the same time as us)

Keeping these in mind, scientists have concluded that if there is an alien civilization existing at the same time as us in the same galaxy, it would have to be at least 33,000 light-years away. To put that into perspective, our Sun is about 27,000 light-years away from us. Yeah. Pretty far.

October 20: Enteral Ventilation

Sometimes, CPR isn’t enough to save respiratory failure. Then, patients turn to mechanical ventilation. But sometimes mechanical ventilation is too much, and the lungs end up even further damaged. Enteral ventilation, however, may just be the sweet spot. Enteral ventilation is a practice where perfluorodecalin, an exceptionally oxygen-soluble liquid, is administered through the intestine to deliver oxygen to the body while the lungs heal. Published on October 20, the first in-human study of enteral ventilation succeeded and was demonstrated to be safe. The only side effects were bloating and stomach pain, but those quickly resolved, and perfluorodecalin concentrations nearly disappeared from the bloodstream (a good thing!).

After this safe and tolerated success, more studies on enteral ventilation will soon develop, and lungs everywhere may be saved.

October 20: CI Chondrite on the Moon

Before we get into any of this moon stuff, you may be wondering what in the world (or should I say galaxy) CI Chondrite is. I’m here to help! CI Chondrite, a porous and the most water-dense meteorite, generally breaks before it can reach Earth because its properties make it so crumbly. CI Chondrite actually makes up less than one percent of all meteorites on Earth. That means it also barely ever reaches the moon. However, during their Chang’e-6 mission published on October 21, the China National Space Administration found traces of CI Chondrite dust on the moon.

Here’s how they did it:

- They looked at thousands of fragments from the Apollo Basin, a sub-basin in the South Pole-Aikten Basin that acts as a hotspot for debris since it covers one-fourth of the moon.

- They looked for pieces with olivine, a mineral normally in meteorites.

- Then, they analyzed the olivine pieces and found seven with properties identical to CI Chondrite

- When analyzing, they found that the pieces did not have the chemical ratios expected for lunar debris.

- However, they realized that the seven fragments’ ratios did align with those of a CI Chondrite asteroid that crashed, melted, and solidified on the moon early in the solar system’s history.

With these discoveries, the team found the first solid evidence that CI Chondrite once hit the moon and that CI Chondrite can be preserved after such a crash. Actually, they found that CI Chondrite could comprise up to 30 percent of the Moon’s meteorite debris. Additionally, their study provided evidence to help back up the theory that CI Chondrite once created water and volatiles on the Earth and Moon. More research is needed to see if it’s really true, but those missions will now be much easier with the China National Space Administration’s new process to find CI Chondrite.

October 27: Back to the Basics

Nope, not like the song. On October 27, in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, scientists described their findings of what they believed to be Population III stars, one of the first groups of stars in the galaxy. With the James Webb Space Telescope, they pinpointed them in LAP1-B, a cluster of stars 12 billion light-years away from Earth. Scientists believe Population III stars are some of the first stars made after the Big Bang, and they have a unique property of being a billion times brighter than and a million times the mass of our Sun.

Here’s why they believe their discovered stars to be Population III:

- Emission lines on the stars’ spectra indicated high-energy photons, which are consistent with Population III stars.

- Their spectra showed them to be extremely large.

- Their masses aligned with astronomers’ guesses for those of Population III stars.

- They were in LAP1-B, whose properties agree with the criteria for Population III.

- It’s a low hydrogen and helium environment.

- Its temperature can support star formation.

- It’s a low-mass cluster, and it had few large stars before those of Population III.

- It meets mathematical criteria for forming stars and keeping them alive.

Seems pretty feasible, right? Anyways, these scientists were the first to find a group of stars that meets all criteria for being Population III, and these ancient stars can actually explain the galaxy’s construction and development. That’s all for STEM this October, but don’t worry, because this November’s looking like a great one.