By Gabrielle Eisenberg

~17 minutes

“Not only are plastics polluting our oceans and waterways and killing marine life – it’s in all of us and we can’t escape consuming plastics,” says Marco Lambertini, Director General of WWF International [20].

The emergence of plastic and its accumulation in people and the environment has been a rising global concern for over 80 years, since it first caught the attention of scientists in the 1960s due to the observed effects in marine species [7]. Even more concerning, plastics continue to accumulate on the planet year after year. In 2019, there were a predicted 22 million tons of plastic worldwide, with a projected 44 million tons of plastic polluting our earth within the next 35 years [5].

In particular, humans inhale about 53,700 particles of plastic a year and orally ingest anywhere between 74,000 and 121,000 annually [5]. Plastics production and environmental buildup are surging with modern prosperity and efficiency, posing a serious threat to human reproductive health as they accumulate in critical reproductive organs like the placenta.

Microplastics

“Microplastics could become the most dangerous environmental contamination of the 21st century, with plastic in everything we consume, it may seem helpless.” [18]

Microplastics are tiny particles of plastic that are contained in the air, plastic dust, food, fabrics, table salt, trash, and nearly every part of modern life. They can range from five millimeters to one micrometer (µm) [11]. Even smaller sizes of microplastics, called nanoplastics, pose a threat to human cells. Less than 100 nm in size, nanoplastics can cross all organs, including the placenta and blood system [11]. Microplastics of size ≤ 20 µm can enter any organ, and; ≤ 100 µm can be absorbed from the gut to the liver [11]. Scientists have discovered microplastics in many parts of the human body, including the liver, blood, and other reproductive organs, including the placenta [15].

Microplastics have multiple routes of getting into the body, which makes them a challenging threat for humans to overcome. To begin, they can be absorbed into the body by wearing clothes with fabrics containing plastic, like polyester. Although this most commonly occurs via inhalation of microplastics in the air, emerging theories also suggest that with long enough exposure to intact or open wounds, absorption of nanoplastics through the skin is possible as well. Inhalation can also occur from air pollution, specifically in areas with high carbon dioxide and dust levels.

In addition, microplastics can be consumed through foods we eat, or plastics we drink or touch, like plastic straws. Marine life also consumes a significant amount of microplastics from pollution in the ocean. Importantly for humans, this is an entry point to the food supply, as the contaminated marine life will then pass the microplastics up the food chain to humans when we eat seafood [11]. Moreover, cleaning products and cosmetics can contain a high amount of plastics that are absorbed into the skin [11]. Some estimates say that a credit card’s worth of microplastics is inhaled by an individual human every week [2].

A practical solution would be to pass the microplastics in the stool; however, the plastics do not always leave the body via waste. Sometimes, microplastics accumulate in the body over long periods of time and absorb into the intestines, bloodstream, and other tissues. Microplastics tend to find their way into crucial arteries and tissues due to their molecular composition.

They are made of synthetic polymers, a series of repeating monomers. The monomers in microplastics are made up of carbon and hydrogen atoms and occasionally have oxygen, nitrogen, chlorine, or sulfur atoms inside [3]. Some of the main components of microplastics are their polymer chains because, like polyethylene, they contain monomers like (–CH₂–CH₂–)ₙ [3]. Also, plastics usually contain additives to enhance their usual properties, but they also have harmful effects on humans. For example, phthalates, which make polyethylene flexible, negatively impact reproductive signals, while colorants are not chemically bonded to the polymer, and thus escape into the environment [3]. Most importantly, microplastics are mostly hydrophobic, which means they repel against water. This causes them to bind with oily substances and bioaccumulate in human tissues [3].

Female Reproductive System

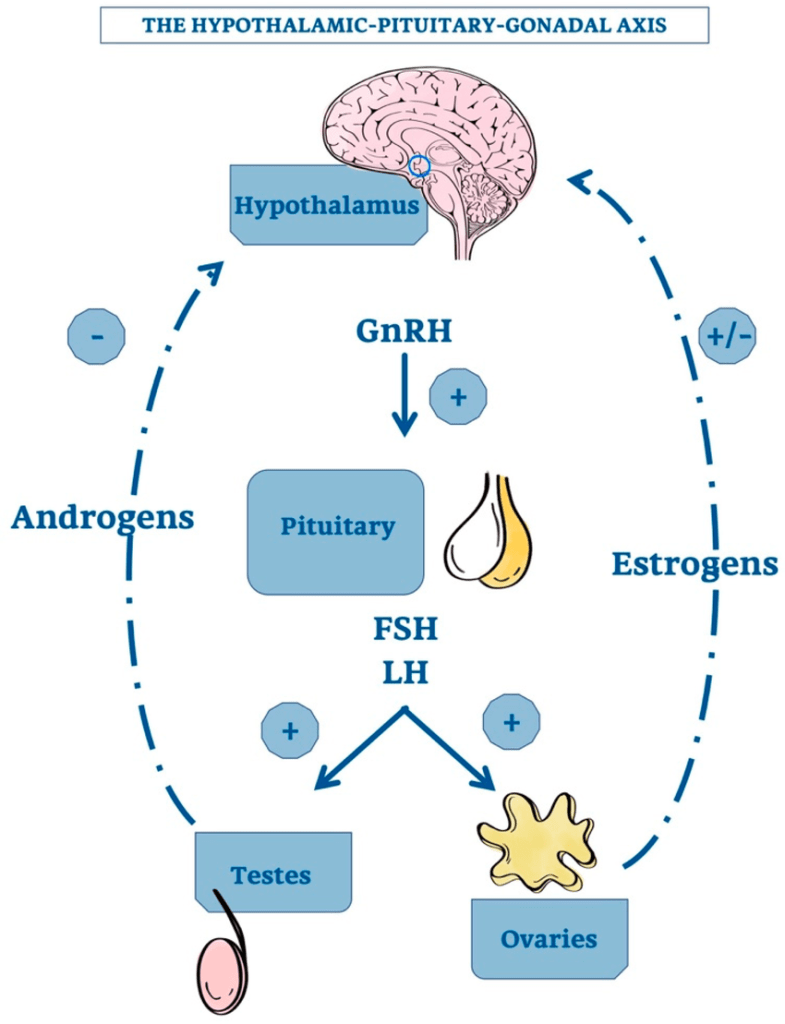

The reproductive system is a highly complex system requiring the coordination between several organ systems and the endocrine system to ensure the human body is an adequate environment for fetal development. The hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, located between the brain and reproductive organs helps to control ovulation and coordinate reproductive behavior [8].

First, a primary signal called the GnRH (gonadotropin-releasing hormone) is produced by the hypothalamic neurons, which stimulates the pituitary gland to release two important hormones: FSH (follicle–a fluid filled sac in the ovary that contains the immature egg–stimulating hormone) and LH (luteinizing hormone) [8]. These hormones lead to ovarian growth, egg maturation, and preparation of the uterine lining for pregnancy [8]. As the follicles grow, they start to make a form of estrogen known as estradiol, which will ultimately slow down the production of GnRH and FSH [8]. Once there is an adequate amount of estradiol, the GnRH and FSH will burst and surge, leading to ovulation. These reproductive hormones, such as GnRH, regulate the proper timing of a woman’s reproductive cycle [8].

However, foreign chemicals, microplastics, and agents can interfere with hormonal signals, either blocking or mimicking them. This disruption can cause infertility, irregular menstrual cycles, and complications in fetal development, since hormones are key to regulating and protecting the growth of vital organs like the baby’s brain and heart [8].

The placenta forms in a woman during pregnancy. The placenta is crucial for fetal development as it connects the fetal and maternal circulations via the umbilical cord. It supports the baby’s growth and development by providing nutrition and removing waste from the baby’s blood. In addition, the organ plays a major role in immunity because it helps the fetus identify self versus non-self cells and antigens. The placenta is located on the wall of the uterus lining and usually on the top, side, and sometimes even the lower area. When the placenta is too low, it raises a risk known as placenta previa, which is caused when the organ covers the cervical opening, and it can develop this way if microplastics were to block and change growth signaling for the placenta [14].

Microplastics in Female Reproduction

Microplastics enter the human placenta through many of the same pathways they use to accumulate in other tissues. First, they can be introduced through food consumption or inhalation [2]. Then, particles are absorbed through the gut and travel into the bloodstream, where they find their way into the placenta during pregnancy.

On a molecular level, after entering the body, their hydrophobic polymer chains prevent normal decomposition [2]. This means microplastics can proceed and bind to other toxins such as heavy metals, which can enhance the harmful effects in living organisms. Once inside the body, the microplastics can cross membranes such as those in the gut, like the M-cells in the intestinal lining, through the cellular process of endocytosis, which can take in foreign particles [2]. From there, they can enter the lymphatic system and/or the bloodstream [2].

Another pathway for microplastics is that sometimes they can bypass the digestive system completely through cells or between cells transport, which is also known as trans-cellular and paracellular transport [2]. Once in the bloodstream, microplastics can circulate to any part of the body, including the placenta. While the placenta does have a layer to protect it from harmful substances called a syncytiotrophoblast layer, nanoplastics can bypass this layer through endocytosis or passive diffusion through functional surfaces coated with proteins [2].

Once inside, the microplastics may interact with intracellular structures like the mitochondria, which can affect energy production, the endoplasmic reticulum, and as a result impact protein synthesis and lysosomes, ultimately leading to cell damage [2]. Studies show high levels of microplastics in human placental tissue:

In a 2024 study led by Dr. Matthew Campen and colleagues, microplastics were found in all 64 placentas studied, with amounts ranging from 6.5 to 790 micrograms per gram of tissue. Moreover, it was found that 54% of the plastic was polyethylene, the plastic that makes up plastic bags and bottles, with polyvinyl chloride and nylon being 10%, and the rest being nine other polymers [13]. This suggests that a majority of the placental microplastics are likely inhaled due to direct contact with the plastics on our mouth, nose, hands, etc.

Another study showed that 10.9% of all microplastics found in a human body were in the placenta, demonstrating how common microplastic exposure is during human development [5]. Thus, microplastics can enter the developing fetus through the placenta [13]. Multiple international studies have found microplastics within the placenta and neonatal samples, suggesting a widespread exposure of microplastics globally [4]. Between 2021 and 2023, seven studies were conducted in four countries, which showed a high percentage of microplastics in the placental tissue.

In 2021, an Italian study identified microplastics in four out of six placentas from vaginal births using light microscopy and Raman microspectroscopy [9]. In another Italian study, all ten placentas (from both vaginal and Cesarean section births) contained microplastics [9]. Electron microscopy revealed cellular damage, although the association with microplastics was not definitive [9]. Importantly, higher microplastics and polymer levels were linked to greater water consumption and frequent use of certain personal care products [9].

In 2022, an Iranian study detected microplastics in 13/13 placentas from the intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) group and only 4/30 in the normal group [9]. This study implied that microplastic exposure may affect fetal development and normal growth. More studies also showed the presence of microplastics in cord blood samples [4]. However, only a few were tested since there is no commercially available test to find microplastics in placentas. These studies demonstrate that, as reproduction continues, this cycle could lead to a growing buildup of microplastics in future offspring and a possibility of new illnesses that will go unnoticed.

Placental microplastics affect reproduction and early fetal development. Fetal development begins from the first stage of pregnancy, often before many women realize they are pregnant [19]. There are three stages of fetal development: germinal, embryonic, and fetal [19]. The germinal stage is where the sperm and egg combine to form the zygote [19]. From there, the zygote turns into a blastocyst, where it is implanted into the uterus [19]. Next is the embryonic stage, usually from around the third week of pregnancy to the eighth week [19]. During this stage, the blastocyst becomes an embryo as the baby develops human characteristics such as organs [19]. At weeks five to six, the heart is recognized in the baby, and little arm and leg stubs are also discoverable [19]. Finally, the fetal stage begins around the ninth week and lasts until birth. During the fetal stage, the baby develops its primary sex characteristics that officially turn the embryo into a fetus. The fetus also grows hair and fingernails at this time and can start to move [19].

Microplastics can affect fetal development in several ways. Ultimately, babies are born pre-polluted [12].

“If we are seeing effects on placentas, then all mammalian life on this planet could be impacted,” says Dr. Matthew Campen, Regents’ Professor, UNM Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences.

Once the microplastics and nanoplastics enter cells, including both germ and somatic cells, they can cause oxidative damage, which can lead to DNA damage and cell death [16].

Microplastics can lead to cell death through pyroptosis [16], a highly inflammatory form of lytic programmed cell death caused by microbial infection [17]. When microplastics are detected, there is trafficking of immune cells like natural killer, T cells, and uterine dendritic cells to extinguish them as they are detected as non-self [16]. In mouse models, placental microplastics were shown to reduce the number of live births, alter the sex ratio of offspring, and cause fetal growth restriction, all effects that have also been observed in humans.

If one of these effects is already seen in humans, it raises the possibility that the others could follow. Since microplastics are present in human tissues, the outcomes seen in animal models like hormonal disruption, reduced sperm count and viability, decreased egg quality, neurophysiological and cognitive deficits, and disrupted embryonic development, [1] could also emerge in humans.

Furthermore, microplastics can change the gut microbiome and hormonal signaling, which can directly impact normal physiology and alter the signals sent between the uterus and embryo [1]. They do this by changing the balance and composition of the gut, which can lead to dysbiosis, an imbalance of the gut bacteria [10]. Some changes to the delicate gut microbiome could cause a condition called leaky gut, which shifts the previously semi-permeable membrane into a hyperpermeable one [10]. Emerging research demonstrates increasing rates of infertility, with scientists implicating environmental exposures, including microplastics.

Microplastics may also affect the endocrine system, which leads to neurodevelopmental issues in the offspring [1]. Another feature of abnormal pregnancies can be high blood pressure in mothers (like preeclampsia), which can result in organ failure and severe problems in the mother [1]. The endocrine system is the hormone-regulating system in your body that directly involves the glands of the gonads (ovaries and testes). Microplastics can interfere with the production of these hormones due to the additive factors the polymers carry, like Bisphenol A (BPA), which is used to harden the plastic [1].

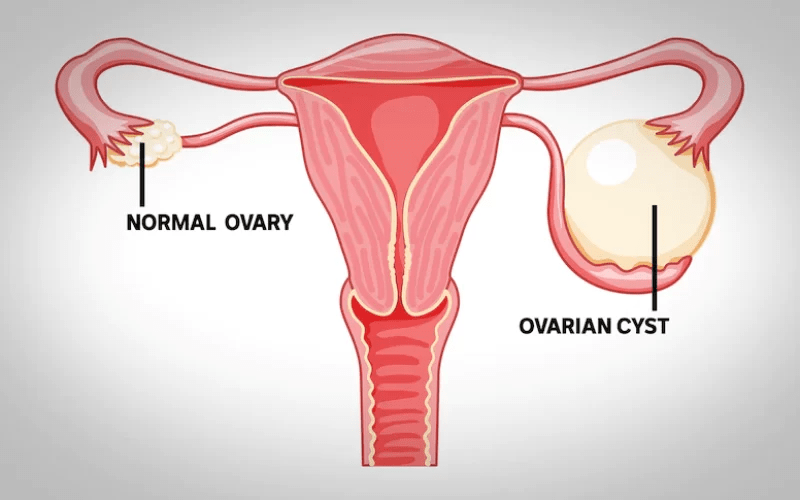

These chemicals are known as endocrine-disrupting chemicals. In addition to this, it can directly bind to the hormone receptors and block normal signaling [1]. Such effects can change gene expression, cause hormone-related cancers, and most importantly, impact fetal endocrine function and development, including lower birth weight and reproductive disorders [1]. Ovarian cysts—fluid-filled sacs that develop on or in the ovaries—can also be caused by microplastics in the reproductive system [15]. When a hormone signal is out of balance, it can trigger the egg not to be released, which can persist to form a cyst [15]. Although this is still being researched by scientists today, there has been a direct correlation in mice, suggesting microplastics disrupt ovarian follicle development.

While the immediate effects of microplastics in placentas are concerning, there are other long-term concerns, such as a generational impact, that raise a sense of urgency to the issue. First, microplastics do not disappear once a person dies [6]. The synthetic particles of microplastics resist biodegradation when the body is buried or even cremated [6]. This means it can reenter the ecosystem and harm other organisms [6]. On the other hand, microplastics are also being passed from generation to generation through parental gametes and the placenta. Microplastics can lead to more detrimental impacts that haven’t even been discovered yet. With more and more accumulation, the body can respond in many different ways that are hard to predict. However, it can be assumed that populations with more microplastics are more likely to be infertile in the future. One can imagine a scenario in which natural selection might occur, as people with less microplastics or who are less affected by their presence will be better able to survive and reproduce.

Summary and Conclusion

Microplastics lead to hormone imbalances of estrogen and other hormones in female bodies by disrupting hormone signaling (activating and blocking), and altering reproductive organ function and development, including infant birth weight, length, and head circumference [10]. Microplastics can interfere with gene expression or epigenetic markers, which can alter the way a fetus develops [10]. They can cut gene readings short, which could lead to affecting their length or head circumference [10]. Impaired egg development and follicular growth can impair fertility and have been linked with microplastic exposure [10]. Similarities can be seen in male fertility as microplastics affect the inflammatory response, change hormone levels with their disrupting and toxic chemicals, and cause cellular damage to the development of the gametes [5]. Overall, the effects of microplastics on reproductive systems have grave consequences, with evidence suggesting infertility in humans.

In addition to understanding the effects of microplastics on human health and reproduction, scientists are working to rid the body of microplastics. By studying plastic-eating microorganisms, they can examine the enzymes they have that allow them to process microplastics naturally [10]. Additionally, as there is increasing understanding of methods of exposure, such as inhalation or absorption, [10], there are ways to reduce the chance of microplastic exposure to your body. For example, humans face the biggest possibility of exposure from food. Fish is a great source of nutrients and protein, however, it is extremely crucial to know that fish carry large quantities of microplastics ingested in the ocean. By ensuring trash and plastics do not end up in aquatic ecosystems, humans can reduce the chance of microplastics entering the food chain. Scientists are also advocating for the elimination of single-use plastic and finding a more sustainable way to save the human population and the environment.

Leave a comment